Imagine two worlds, two cradles of civilization separated not just by thousands of miles of ocean and land, but by the chasm of our traditional historical narrative. In one corner, Mesopotamia, the fertile crescent between the Tigris and the Euphrates, where Sumer flourished. In the other, the vast American continent, home to civilizations as enigmatic as the Olmecs in the Mexican jungles and the Andean cultures in Peru. The official narrative tells us that these two universes developed in splendid isolation.

But what if that narrative is incomplete? What if subtle but persistent threads existed, connecting these two poles of human ingenuity across the great ocean? This isn’t a mere academic exercise. It’s an immersion into a mystery that challenges our certainties, a journey to explore anomalous clues that suggest an astonishing possibility: ancient contact between Sumerians and the Americas.

Prepare to question the map of the ancient world you thought you knew. Together, we’ll follow the trail of these historical whispers not to find definitive answers, but to learn how to ask deeper, more audacious questions.

Artifacts Whispering Across the Ocean

The most tangible, yet most controversial, evidence of this transoceanic connection isn’t found in a grand monument, but in humble objects that seem to tell an impossible story. These are pieces that don’t fit, anomalies that act as keys capable of unlocking a radically different past.

The Fuente Magna: An Andean Rosetta Stone?

Near Lake Titicaca in Bolivia, a piece has been both revered and ridiculed: the Fuente Magna. It’s a large ceremonial-looking ceramic bowl, covered with inscriptions on the inside. What makes it historical dynamite is that part of the writing has been identified by some epigraphers as Proto-Sumerian cuneiform script.

The controversy is immediate and fierce. Mainstream archaeology considers it, at best, a piece with misinterpreted inscriptions or, at worst, a modern forgery. However, for those who dare to consider it authentic, the Fuente Magna is an artifact as important as the Rosetta Stone.

🔎 Evidence Profile: Analysis by researchers like Clyde Winters suggests the bowl’s inscriptions contain not only Proto-Sumerian glyphs but also motifs from the Tiahuanaco culture, suggesting a cultural syncretism. Proposed translations speak of purification rituals and devotion to a goddess named Nia, whose phonetics evoke Sumerian deities like Inanna. The piece appears to be a manual for connecting with the divine, written in a language that, theoretically, should never have reached South America.

The bowl is not just clay and carvings; it’s a vessel that holds a question threatening to break the paradigm of isolation. If authentic, who brought it? A group of traders, exiles, or explorers? And what knowledge did they bring with them, besides their writing?

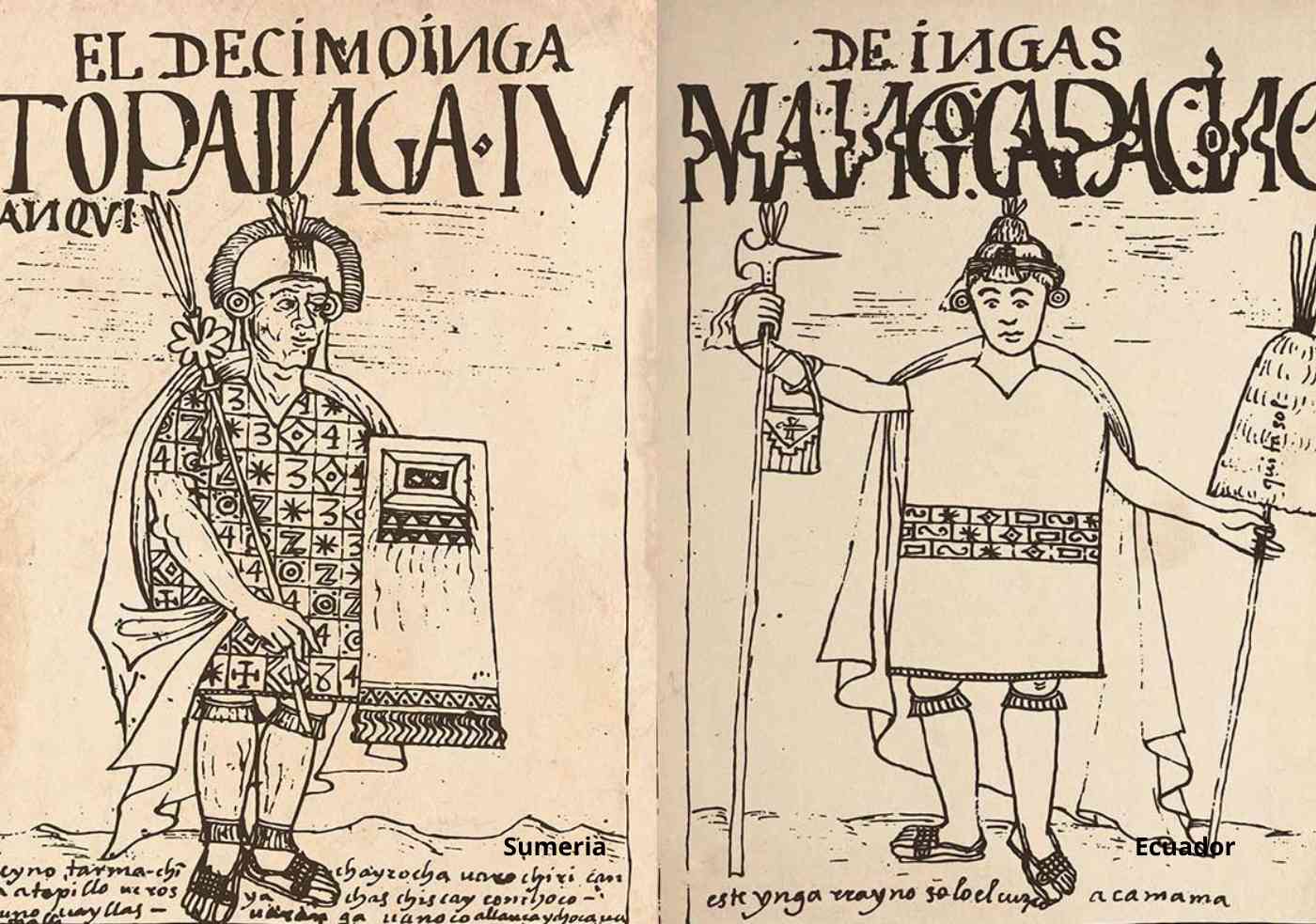

The Pokotia Monolith and the Ecuadorian Statue: Out-of-Place Effigies

Near where the Fuente Magna was found, another enigmatic piece emerged: the Pokotia Monolith. This stone stele, though rough in its carving, features inscriptions similar to those on the bowl and an iconography that, to some eyes, evokes Mesopotamian art. The central figure, with its large eyes and hieratic posture, feels alien to the pre-Inca Andean artistic canon.

Further north, in Ecuador, a statuette was discovered that adds another layer to the mystery. The figure, with its conical headdress and formal style, bears an astonishing resemblance to representations of Sumerian goddesses. Its presence on South American soil is a geographical and cultural anomaly that demands an explanation.

These aren’t just carved rocks. Imagine them as fingerprints of travelers, as cultural beacons left on a distant coast. Their mere presence forces us to question the model of a disconnected ancient world and pushes us to imagine the bold journeys that might have brought them here. They are the possible fossils of a meeting, petrified proof that oceans were not always barriers, but also pathways.

A Shared Blueprint: Architecture and Cosmos

If small artifacts are whispers, great constructions are declarations shouted to the sky. It is in monumental architecture and the conception of the cosmos where the similarities between Sumer and Peru become even more intriguing, suggesting not just possible contact, but a shared matrix of thought.

Ziggurats and Huacas: The Universal Impulse to Touch the Sky

Travel 5,000 years back in time to the Supe Valley in Peru. Here stands the sacred city of Caral, the oldest civilization in the Americas. Its heart is formed by imposing stepped pyramids, superimposed platforms that rise toward the desert sky. Now, mentally cross the globe to ancient Mesopotamia. What do we see? Ziggurats, stepped pyramid towers that dominated cities like Ur or Babylon. The conceptual similarity is striking.

Although materials (adobe in Mesopotamia, stone and earth in Caral) and exact functions (temples on top of ziggurats, ceremonial platforms, and elite residences on Caral’s pyramids) differ, the fundamental idea is identical.

- Stepped Structure: Both cultures chose not to build pyramids with smooth faces, but structures in terraces, like a stairway to the gods.

- Cosmic Axis Function: Both the ziggurat and the Andean huaca or pyramid functioned as an *axis mundi*, a sacred point of connection between the world of men, the underworld, and the celestial world.

- Astronomical Orientation: Many of these structures, including those of Tiahuanaco and the Sumerians, are precisely aligned with solsticial or equinoctial events, demonstrating an advanced knowledge of the cosmos.

The similarity lies not in the bricks or the exact technique, but in the fundamental idea: the construction of an artificial mountain, a cosmic axis to connect the earthly plane with the divine. It is an echo of a spiritual yearning that seems to transcend cultures and oceans, a shared mental blueprint for approaching the sacred.

The Sun as a Central Deity: When Inti Reflects Utu

The cosmic connection doesn’t end in stone; it extends to theology. The Sumerians venerated Utu (later known as Shamash by the Akkadians), the god of the Sun, justice, and truth. Utu was the one who emerged each morning from the eastern mountains, bringing light and order to the world. In the Andean pantheon, and especially among the Incas, the supreme deity was Inti, the Sun god, divine ancestor of royalty and source of all life, warmth, and agriculture.

📊 Impactful Fact: In both empires, the priestly caste not only directed solar rituals but also administered the calendar, agriculture, and law. The sun was not just a god; it was the central gear of the entire state machine. The king or emperor, whether in Sumer or the Inca Empire, was often considered the earthly representative of the solar god, his vicar on earth. This fusion of religious, astronomical, and political power around a solar deity is a structural parallel too deep to be ignored.

The Human Imprint: Language, Life, and a Controversial Legacy

Beyond stone and pantheons, the most intimate and debated connections are found in the traces we leave as human beings: our language, our rituals for the dead, and the stories we tell about our own past, however fantastical they may seem.

Traces in the Voice: Linguistic Echoes from En-ki to Inka

This is perhaps the most slippery and fascinating ground. Some heterodox linguists have pointed to surprising phonetic and semantic parallels between Sumerian (an isolated language with no known relatives) and Andean languages like Quechua or Aymara. The most cited connection is that of the Sumerian god of knowledge and waters, En-Ki, and the title of the Andean emperor, Inka or Inqa.

Other examples include words related to agriculture, royalty, or topography. Academic linguistics largely rejects these connections, attributing them to coincidence or flawed methodology. However, the volume of these apparent coincidences continues to fuel speculation.

The Transatlantic Mystery of Coca and Mummies

In the 1990s, German toxicologist Svetla Balabanova made a discovery that should have rewritten history books: analyzing Egyptian mummies from the Twenty-first Dynasty, she found traces of cocaine and nicotine, substances from plants that, as far as we know, only grew in the Americas. The finding was corroborated by multiple laboratories but quickly relegated to the category of “unexplainable anomaly.”

This botanical thread intertwines with another shared practice: mummification. Both ancient Peruvians (notably the Chinchorro culture, which practiced mummification thousands of years before the Egyptians) and the Sumerians and Egyptians had complex rituals to preserve the bodies of the dead, believing in an afterlife. Although the techniques varied drastically, the fundamental intention of preparing the body for a post-mortem journey is a powerful conceptual link.

✨ Deep Connection: Coca doesn’t travel alone. With it travel botany, pharmacology, rituals, and trade routes. This finding doesn’t suggest a simple exchange, but a network of knowledge that could have connected the Andean valleys with the Nile, demonstrating that the ancient oceans were bridges, not barriers. The Egyptian mummy with traces of coca is the silent witness to a global trade that completely defies our accepted chronology.

The Library of Ica: Monumental Hoax or Forbidden History?

No exploration of anomalous connections in Peru would be complete without mentioning the famous and controversial Ica Stones. This is a collection of thousands of andesite stones engraved with scenes that look like they’re from a science fiction novel: men performing complex heart and brain surgeries, using telescopes to observe the stars, and, most shockingly of all, living with dinosaurs.

It is crucial to state that the scientific and archaeological community overwhelmingly considers the Ica Stones an elaborate hoax, created by local farmers starting in the 1960s. However, their cultural impact is undeniable. They represent the crystallization of a yearning for a lost history, an “antediluvian” golden age of knowledge.

One God, Three Civilizations: The Echo of the Staff God

The enigmatic figure of the “Staff God,” immortalized on the Gate of the Sun at Tiahuanaco, is not a solitary echo in the history of faith. His image, that of a central deity wielding symbols of dual power, resonates surprisingly with representations of the great gods of Sumer and Egypt. In Mesopotamia, deities like Enki or Marduk granted kings the “scepter and the ring,” emblems of divine law and cosmic order, a power delegated from on high. In a parallel way, in the Egyptian pantheon, primordial gods like Osiris exercised their dominion over life and death by holding the crook and flail in their hands, two scepters that embodied their royal and divine authority.

More than a simple artistic coincidence, this recurrence of the “Lord of the Two Scepters” archetype in such distant cultures suggests a common theological substrate: a fractured ancestral memory of a single creator God, whose power over heaven and earth was symbolized through these staffs of command.

Beyond the Andes: The Long Shadow Over Mesoamerica

The trail of these possible connections is not limited to the Andean highlands. If we turn our gaze north, to the humid and lush lands of the Gulf of Mexico, we find what is considered the “Mother Culture” of Mesoamerica: the Olmecs. And it is here, among their colossal stone heads and their enigmatic altars, where the echoes of a distant world become particularly resonant.

The Olmecs and the “Bearded Men”: An Unexpected Face in the Jungle

One of the most persistent enigmas of pre-Hispanic art is the representation of men with beards. Genetically, native American populations have sparse facial hair. However, in the Olmec artistic record and in later cultures influenced by them, such as the Mayans, figures with long, well-groomed beards appear, a typical feature of Old World peoples like the Sumerians, Akkadians, and Phoenicians.

Monuments like Stela 3 of La Venta show a main character, presumably a ruler or priest, interacting with another figure who has a prominent beard. These are not abstract representations; they are detailed portraits of a physical type that, quite simply, shouldn’t be there. Skeptics argue that they could be masks or false beards, but the consistency and naturalism of these representations in multiple artifacts suggest that the Olmec artists were portraying people they had seen.

These “bearded men” petrified in stone confront us with an unavoidable question: who were they? We cannot avoid thinking of the figure of the “civilizing hero,” that mythical character, often described as a bearded foreigner, who arrives from the sea to bring knowledge, law, and the arts to a people. From the Andean Viracocha to the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl, the archetype resonates. Are these stelae the historical portrait of the bearers of a Sumerian or Semitic influence?

Echoes in Writing and Power

The connection is not just physiognomic, but also structural. The Olmecs were the precursors in Mesoamerica of concepts that were the pillar of Sumerian civilization:

- The Idea of the City-State: Urban centers like San Lorenzo or La Venta functioned as political and religious nuclei that exerted power over a surrounding territory, a model identical to that of the Sumerian city-states of Ur, Uruk, or Eridu.

- The Invention of Writing: Although Olmec writing (possibly recorded on the Cascajal Block) is hieroglyphic and visually distinct from cuneiform, the conceptual leap is the same. It represents the first time in America that a codified system was used to record information, a technological advance that transforms society.

- Deified Royalty: The Olmec ruler, like the Sumerian king, was not a simple political leader. He was a mediator between the human world and the cosmos, a shaman-king whose power emanated from his connection with divine forces and ancestors.

Weaving the Threads of a Forgotten History

At the end of this journey, the puzzle has become larger and more complex. To the Andean pieces the bowl with impossible writing, the pyramids that echo across the deserts, and the plants that navigated forbidden routes are now added the bearded faces of the Olmec jungle and the shared blueprints of divine royalty and the power of writing.

Each thread, on its own, can be discarded. But when woven together, the tapestry that emerges is no longer regional, but continental. It shows us a past where oceans might not have been barriers, but highways for the exchange of genes, technology, and sacred ideas.

The question, then, resonates louder than ever: are we simply facing a series of astonishing coincidences, inevitable products of the universal logic of human development? Or are we, perhaps, contemplating the eroded footprints of a lost chapter of our global history, an era of bold navigators whose achievements in Peru, Mexico, and beyond, we are only just beginning to imagine?